A study published in the prestigious journal Science seems to reveal an important new secret of cuprates, copper-based materials that can carry electrical currents without resistance even at very low temperatures and therefore can potentially cut the costs of electricity distribution across the world.

The study – carried out by researchers at the Polytechnic University of Milan, Sapienza University of Rome and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) – has shed new light on some key behaviours of these superconductors in the so-called “normal state”, i.e. at temperatures above the superconducting critical temperature.

An important property of cuprates is that in their normal state they tend to behave in a non-conventional way compared to other metals and therefore they are referred to as “strange” metals. The strangeness of cuprates lies in the fact that their resistivity rises linearly with increasing temperature. This phenomenon, which does not occur in normal metals, has been investigated by many international research groups in recent years.

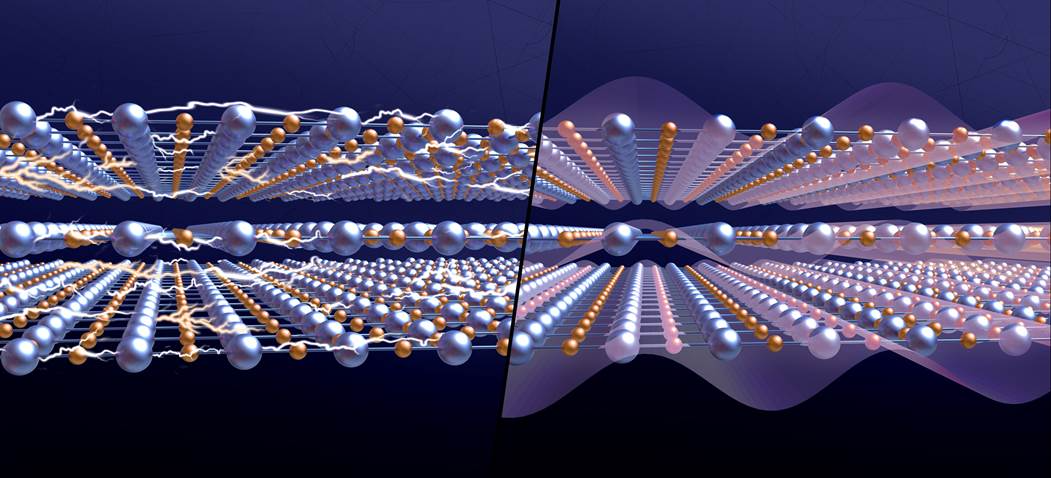

The present study, published in Science, showed that, in the normal state, the presence of charge density waves modifies the behaviour of cuprates bringing it more into line with that of normal metals. “This type of observation is highly significant because it finally shows a correlation between macroscopic properties (resistivity in the normal state, superconductivity) and microscopic properties (charge density waves),” explained Giacomo Ghiringhelli, professor of Experimental Physics at the Polytechnic University of Milan. “This may be the key to the problem long sought after by theoreticians, a solid foundation on which to finally build an explanation for the unconventional behaviour of cuprate superconductors,” Ghiringhelli concluded.

The study has also contributed to reinforcing the idea that the phenomenon of superconductivity partly responds to the laws of quantum physics and that the behaviour of cuprates in the normal state, i.e. at high temperatures, is a macroscopic manifestation of quantum phenomena, the reason why scientists refer to these compounds as “ultra-quantum” matter”.

Source: Politecnico di Milano